Yesterday the Nobel Economics Prize was awarded to David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens for their "contributions to labour economics" and "methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships" respectively.

Indeed, the news reminded me of some fond memories from my university days. Let's start with Jörn-Steffen Pischke's Labour Economics class. No fan of PowerPoint (who is?), he was most effective with a pen and a whiteboard. Problem sets had a decidedly empirical bent and almost always featured some use of Stata. Naturally, Card’s clever exploitation of events as natural experiments - from Mariel boatlift to state borders in the US - featured quite a bit.

But for the great majority of economists who did not do EC317 in the LSE, Pischke is probably best known for the funny yet practical (text)books he jointly wrote with the newly laureled Angrist.

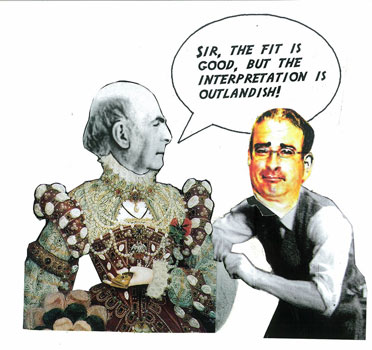

Oh yes, if you're still wondering: yes, I just stole a cartoon from their Mostly Harmless Econometrics. In both economics and fashion it's essential that the model fits, but interpretation is very important too.

Let's get back to Angrist before we digress too much. Indeed, I sometimes wonder how many students have been impressed by the Angrist and Krueger (1991) when they first came across it.

The paper couldn't be more relevant to a student: “ what extent schooling is just an expensive signalling system, and to what extent does it actually increase earnings?”, the authors asked. The instrumental variable (IV) they used - when pupils could legally leave school across US states - is among the most elegant as natural experiments go. As a boon, it then gracefully reassured young readers their schooling had not been totally wasteful to society.

Alas, good things don't last. Subsequent studies found their instruments too weakly correlated with schooling to be robust. Nowadays, the paper features in lecture notes also as a cautionary tale: weak instruments can be worse than no instruments.

This by no means diminishes their pioneering work in investigating causal relationships by exploiting natural experiments with clever statistics.

To paraphrase T.R. Roosevelt, the credit belongs to those who are actually in the arena, who err and come short, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming, etc. And if the world is to move forward at all, it does so mostly by trial-and-error.

The Nobel Committee cannot be more right in recognising their “methodological contributions”: they might have got some answers wrong, but the path forward they laid endures.

|

| My favourite illustration from Mostly Harmless Econometrics |

===

P.S. There's also a fine article on today's FT by Tim Harford on the same topic.